This article was originally published in italian on September 5th.

Localisation is a fundamental component of video games. Without it, a video game would have greater difficulty in reaching new markets and being understood by a more significant number of people.

Yet, the work of so many people involved in the translation of game texts goes unrecognised. Many companies hide the names of freelance translators and have non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) drawn up that prevent professionals from talking about the games they have worked on. In this way, they maintain extensive control over translators’ careers.

To find out the underlying dynamics behind the non-accreditation of freelance translators’ work, I have spoken to seven people over the last few months, most of whom preferred to remain anonymous to prevent what they told me from harming their careers or because the information did not need to be public.

A homogeneous scenario emerged: the larger agencies avoided including the names of the people who worked on the translations, prevented them from talking about it publicly or from including the name of the game they worked on in their CV.

Not only that: in some of the cases, I have been told, the wages are low, and it is implicitly required to work on weekends in order to meet the tight deadlines – often imposed by the end customers (developers or publishers) and not by the agencies, who, in order not to lose a customer, shift the burden of unfavourable working conditions onto the last link in the chain.

The result is that freelance translators working for major localisation agencies cannot make a career for themselves – as they cannot prove that they have worked on many games, often high-budget and therefore appealing – and they remain stuck in the fence that these companies have created to control translators and essentially prevent them from competing on certain projects.

Control and the exercise of power are the two keywords.

The slalom between agencies, NDAs, and demanding clients

A person who has worked on games for companies such as Atlus, Epic Games, Resolution Games and 17-bit told me: “I haven’t been credited for any of the work I’ve done for agencies“.

Another person I spoke with has worked on 70 games for various agencies from 2017 to the present; in 65 games, this person is not in the credits.

“In 99% of the games I have worked on, I am not in the credits,” said a third person.

“I have worked on about 60 games. I’m credited for some of it, but most not”, said Marc Eybert-Guillon, translator and director of From the Void, which localises games in French. “I know colleagues who’ve been in the industry for more than a decade, have translated hundreds of games and only have a handful of credits to their names”.

It is a common practice. So common as to be an open secret: something that everyone working in the industry knows, but against which, individually or as small groups, not much can be done.

One of the first effects of the non-recognition of translators’ work is that it becomes very difficult to assure a new client, such as another agency, of one’s real work experience. At the end of the day, it is a ‘ghost job’: it is performed, it is paid (not always adequately), but it cannot be told publicly.

In the absence of career advancement, getting out of the loop of agencies that do not recognise the work but receive many assignments (and thus become central to continuing to work as a translator) becomes impossible: a vicious circle that forces many people working in localisation to continue feeding the mechanism that blocks them.

One of the main blocks are the non-disclosure agreements (NDA) that are signed. The signing of an NDA is a crucial step to work with an agency that has been commissioned to localise a video game that has not yet been released: during localisation, translators receive parts of the game, such as dialogue and character names, that must not leak out; therefore, companies must ensure that translators sign confidentiality agreements.

The real problem is another: translators are asked not to speak openly about having worked on a game even after it has been published.

To circumnavigate the impossibility of speaking specifically about a video game, even when it has been out for years, translators can, however, provide generic, but understandable enough descriptions to be able to share on their professional social profiles or to other clients about their work experience.

“Usually, it is done like this: you try to give an anonymous but accurate description of a title, so that the customer understands, because they work in the field and are up to date with the releases, maybe even putting the year the game was released,” reported one of the people I interviewed.

Otherwise, you can ask for a reference; but as with other dynamics in the industry, it depends on the agency. “They can send a reference letter stating that I have worked for them, with the number of words translated and an anonymised list of the games I have worked on.”

“As my name is not in the credits and the games’ devs do not know I was involved, actually proving I worked on it would require providing an internal working file or something like that only the localisation team had access to, which would be considered a breach of confidentiality”, said Eybert-Guillon.

“If you are not in the acknowledgements, it is considered quite improper to cite titles,” said another person. “At best, you pass for someone who ignores NDAs, at worst for a dick.”

In many cases, the people working on a translation also do not know beforehand whether they will be mentioned or not. In fact, the inclusion of translators’ names in the credits does not always depend on the agency, but also on the client; the longer the chain, the more chances there are that the policy of one of the companies involved does not provide for translators to be recognised. Sometimes it is the publisher of the game who does not foresee the names of the translators in the acknowledgements; sometimes, it is the developer, and sometimes, as is often the case, it is the agency that did the localization. And asking who made the decision leads nowhere. “In general, when I was told no, they did not explain why or who had chosen,” reported one of the people. “I happened to ask, and there was no way.”

“I happened to ask for it and be told it was an agency policy,” said another person. “They always talk about the signed NDA, with no flexibility because maybe a new developer, who specifically asks for it, wants it, but the agency doesn’t grant that right and so nothing.”

“There are cases where the agency would like to, but the developer doesn’t want to. And there is really nothing in the credits there,” one of the people told me. “And then there are the cases where the developer wants to, but the agency doesn’t want to. And there is only the agency’s name in the acknowledgements.”

Working conditions – such as deadlines – are often imposed indirectly by the customers, who have less visibility on how the localisation is done. “Some clients just want to send the text, and have it translated for yesterday without having to pay too much, and since those might be big clients, the agency will accept “, explained one of the people.

The customer’s stringent conditions are then pushed down to the lowest levels with direct consequences on the work of those who translate: “We then end up with tighter and tighter deadlines, decreasing rates, no context, PMs expecting us to work on weekends”.

Many localisations need additional work to better understand, for example, the mythology underlying a story or to have more insight into a country’s culture. This involves studies and research, but this part of the work is unpaid, even though it contributes to a more accurate localisation.

“The last game I worked on was a very famous Japanese role-playing game,” said one of the people. “It was a very nice, long and also challenging job because it is a game that requires a lot of adaptation work and not just translation. A translator’s job is not just to take and translate: you often get jobs for which you need your own insights, which are not counted for payment”.

Listening to the various stories, the name of one company came up frequently: Keywords.

About Keywords

Keywords is arguably the world’s largest video game localisation company. It has worked on popular games such as Clash Royale, League of Legends, Assassin’s Creed Syndicate, Deus Ex Mankind Divided and Final Fantasy XV.

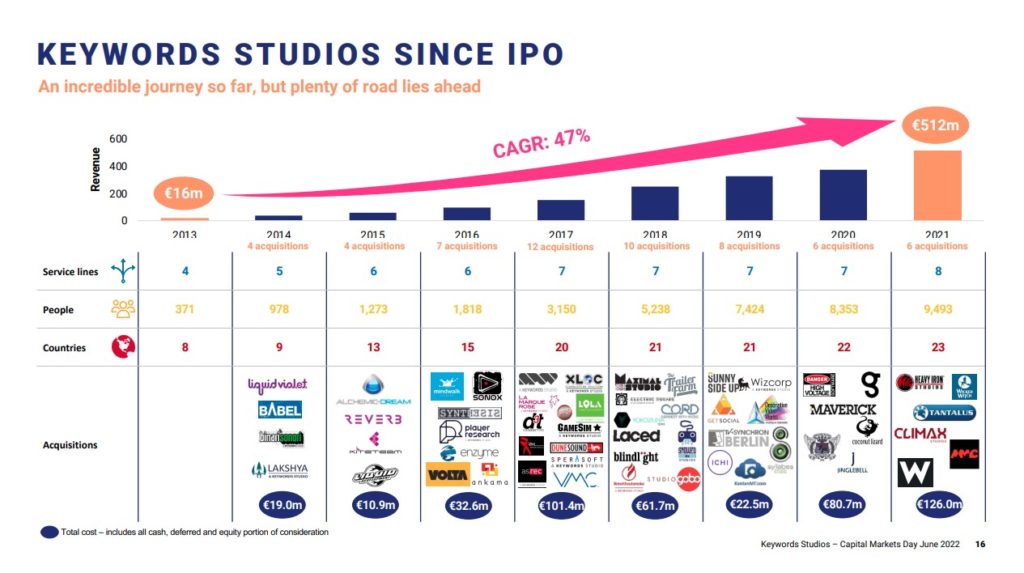

Over the years, it has expanded its international presence by swallowing up many other companies operating in the localisation sector. From 2014 to 2017, it bought Sound Tracks, Reverb, Kite Team, Sonox Audio Solutions, Around the Word, Synthesis Group, Babel Media, Enzyme Testing Labs and VMC. From 2013 to 2021, its turnover grew from $16 million to $512 million, and it grew from 371 to over 9,000 employees.

It recently acquired Forgotten Empires, developer of Age of Empires, and Mighty Games to further expand the number of in-house game development companies. Keywords owns Tantalus Media, High Voltage Software, Climax Studios and Heavy Iron Studios, among others.

Its customers include virtually all of the world’s largest video game companies: Microsoft, Konami, SEGA, Nintendo, Take-Two, Tencent, Bandai Namco, Supercell, Electronic Arts, Ubisoft, NetEase, Warner Bros. and Square-Enix.

In other words: it is almost impossible to work in the industry without coming across Keywords at least once.

At the same time, despite being a company with high visibility, Keywords is also one of the leading companies in the industry that hardly ever mentions who worked on localisation in the final credits.

The reason is easily explained: for Keywords, it is more convenient to convey the idea that it is its service line – of which localisation is only a part – that is the secret to a good project’s success, and not the people who have collaborated. For Keywords, it is more important that there is their brand name instead of the translators’ names.

“People who deal with Keywords know that they have no bargaining power because they are monopolists,” said one of the people, who has worked on many games through Keywords. “People who are trying to get in now are bound to bump into Keywords. In Keywords, you crash, and you remain anonymous, you don’t get work in other agencies, and Keywords will continue to underpay you.”

A further level of complexity is that not all companies in the Keywords group have the same policy. Thus, it may happen that you are mentioned in a project of the Keywords subsidiary in one country, but not in that of another.

“Keywords is a hydra,” summed up one of the people. “When you talk about Keywords, you are talking about a jumble of different studies with different policies”.

This can also happen because the client asked for it, but again, the lack of transparency prevents translators from understanding the underlying dynamics of each project they are involved in.

I contacted Keywords, including the Italian companies that are part of the group, by email and on the phone to ask for comment on the issue. I have never received a reply.

One of the people I spoke to said that they enjoyed working with one of the teams at Keywords. “With the team, you create bonds that lead to better work; the work is coordinated, and there are brainstorming sessions to deal with the most complex situations. From that point of view, I am very satisfied,” this person said, while emphasising that the lack of recognition is the main disadvantage of working with Keywords.

That person has worked almost exclusively with Keywords from 2016 to date on the localisation of 94 games. “In 90 per cent of those, I’m not in the acknowledgements,” they told me. “If I go and look at the list of games where I’m actually in the acknowledgements, absurdly, there are more games where I’m a Kickstarter backer than the ones I’ve translated.”

“When you work for Keywords, for example, you just get the feeling that they accept pretty much everything, and then it’s just about squeezing the last element of the chain, translators, to get it done”, pointed out another person.

I have been able to look at some of the NDAs that some of the companies in the Keywords group have asked their employees to sign over the years. It is expressly defined that it is up to Keywords to grant or not grant permission to translators to talk more or less extensively about a certain game, even after it has been published and then there would be nothing left to hide. This is done on a case-by-case basis and often based on an agreement between a company in the Keywords group and the end customer, a process to which the translator has no visibility.

In another NDA I read, it was written that it is at the agency’s total discretion to decide whether or not to include the translators’ names and that, furthermore, the translators have no claim to it.

NDAs are nothing strange. I have signed several NDA when electronic devices, such as smartphones, game consoles, or even video game codes, have been delivered to me.

These NDAs specify the conditions to be fulfilled (a date before which you cannot spoke or write about, for example) and possible financial penalties if they are not fulfilled. I also happened to sign them for consultancies: the agency wanted to make sure that I did not disclose sensitive information that I would learn about during meetings with clients.

Nothing strange, as I said.

The difference is that, in the case of localisation, some of the conditions included hinder people’s careers. In fact, they are designed to severely slow down careers or even block them.

A devious exercise of power aimed at controlling the careers of translators, especially freelancers, who have only to gain from a rich CV: more games translated equals more opportunities to find work elsewhere.

The centralisation of acknowledgements towards the company – or at most the project managers – allows that company to present itself in front of potential customers as the ace in the hole; as the reality to refer to for a job well done, as if behind it there were not dozens of people, often freelancers, whose work is not recognised.

In this sense, Keywords is the agency that has built its position, most of all, on mergers and acquisitions, becoming the benchmark for localisation services over the years.

A structural problem

To consider the situation as a problem characterising only Keywords would be wrong. In fact, it is a set of bad practices and bad habits that is part of the modus operandi of various agencies and companies.

Two companies where two people I spoke to worked for are MoGi and Transperfect (which acquired MoGi in recent years). One of them worked for six games in MoGi and recounted the difficulty of negotiating fairer wages and also difficult work dynamics; until leaving the company following the acquisition by Transperfect.

“The rate was 0.05 euro per word, but obtained by tooth and nail,” they told me, referring to their time at MoGi. “Then they switched to US dollars, and when I asked to go up to 0.06 dollars for the exchange rate, they made a very sad scene of going to get the exchange rate and ‘proving’ to me that 5 euro cents was less than 6 US cents.”

MoGi’s customers include Bandai Namco, Ubisoft, Annapurna Interactive, Tencent Games, Garena, Capcom, Smilegate and Dotemu.

One of the characteristics of the job was the implicit requirement to work on weekends using underhand and indirect techniques. For example, assigning a certain number of words to be translated on Friday and setting the delivery for Monday morning; a number of words that could not be translated during a single working day. The only solution is to work over the weekend to meet the delivery.

“Since it was taken over by Transperfect, everything has deteriorated: tight and often urgent deadlines; low rates that, if increased, would cause you to lose work and make them stop contacting you; and also work rhythms that are simply absurd,” one of the people added.

The dynamics that before might have been extraordinary – working on weekends, crunch time and below-average wages – became the standard after the takeover.

A second person described MoGi and Transperfect as worse than Keywords because “Transperfect is much further gone down the profit hole, and they’ve always treated translators like complete garbage”.

Neither MoGi nor Transperfect responded to my request for comment.

However, there are other, smaller agencies that recognise the work of the translators and respect their assignment. “We provide all of our clients with a list of all the people who worked on the game”, said Eybert-Guillon on how From the Void works. “If we are not in the credits, it means they’ve failed to implement it, and in this case, we usually push and insist for them to do so. It is our strict policy to ensure everyone gets properly recognised”.

From the Void has mostly worked with publishers and independent developers, who have generally been happy to include translators’ names in the credits. However, even when this is not the case, those who worked on the game’s localisation can speak publicly about it and sponsor their involvement.

Also, Wabbit, a cooperative that has localised various games, has had mostly positive experiences, according to Alice Buratto, translator for Wabbit, who told me. “I don’t think there have been times when we have insisted on being included in the credits. Rather, we happen to ask to appear as the name of the translator + Wabbit Translations instead of just the name of the translator; this request sometimes creates some problems, probably because the name of our team risks distracting attention from the work of the agency, which took care of all the languages’.

It often happens, in fact, that a larger agency may subcontract to a third-party agency, such as Wabbit, a share of the translations, perhaps for specific languages for which it does not have adequate in-house resources.

On one occasion, however, it was Buratto herself who asked not to be included in the credits because”’some of my decisions as reviewer had not been respected and I did not want a work that did not fully reflect the quality I was aiming for to have my name and that of my team on it”.

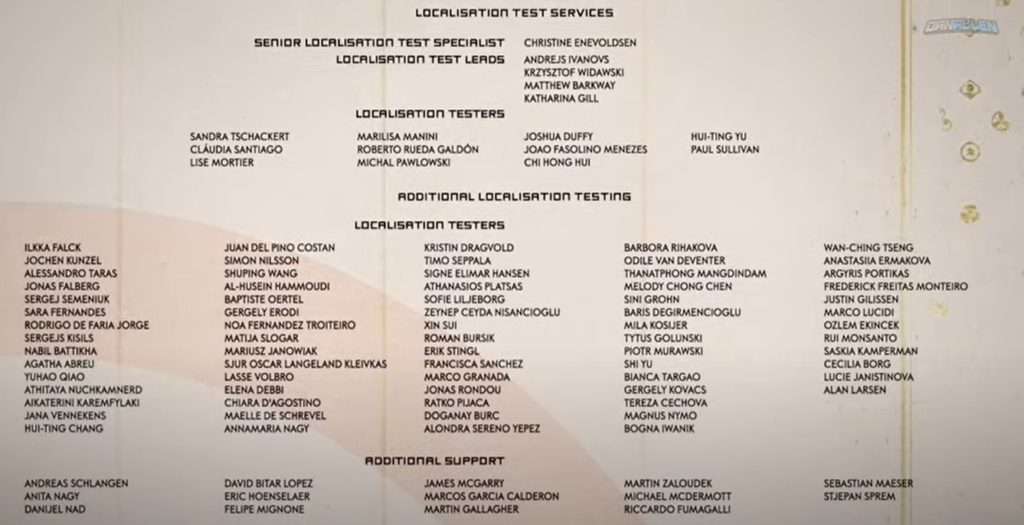

In some cases, as mentioned above, it is the publisher’s or developer’s decision not to have the translators’ names in the acknowledgements, but only that of the so-called “localisation testers” (people who, in a nutshell, check that the localisation works on a technical level and that there are no problems in displaying the texts, for example). Localisation testers are generally internal to the developer or publisher and not external.

Among these companies, one of the most prominent is Sony Interactive Entertainment, which does not mention the translators’ names in its games. I asked Sony Interactive Entertainment Italy for a comment, but they did not reply.

Other companies, such as Square-Enix and Bethesda, seem to be more supportive, and translators’ names are often included in the credits; yet, sometimes, the acknowledgement do not take place, or the agency is in the way.

In essence, the very fact that the policies of so many realities overlap creates situations in which one cannot understand what went wrong and whose responsibility it is.

A recent case in point is Elden Ring, published by Bandai Namco, whose Italian and Spanish localisation was handled by Jinglebell, who worked directly with the publisher. Jinglebell’s CEO, Simone Crosignani, publicly thanked all the people who worked on the localisation on Twitter, mentioning them one by one; yet, in Elden Ring’s credits, the names are not there. Only Keywords France and Jinglebell are credited.

Italian squad: Ivan Fulco, Massimiliano Marino, Leonardo Fedi, Antonio Pizzo, Alessandro De Vita, Stefania Brambilla, Stefano Mozzi, Fabio Tursi, Maneki Commando. Grazie a tutti!

— Simone Crosignani (@Il_Simon) February 25, 2022

On Twitter, Crosignani himself specified, when called upon, that “we always ask for translators, voice actors, audio engineers, QC, etc. to be credited because a) it’s fair and b) I don’t see a single advantage in hiding their names. Not one. Not for Jinglebell, not for them “.

I can't speak for other companies/studios/agencies, but we always ask for translators, voice actors, audio engineers, QC, etc. to be credited because a) it's fair and b) I don't see a single advantage in hiding their names. Not one. Not for Jinglebell, not for them.

— Simone Crosignani (@Il_Simon) April 6, 2022

In a second tweet, after being criticised for taking a job for a company that does not recognise translators, Crosignani wrote that ‘It’s more about survival than growing your company. Choosing not to work with publishers that credit all translators in all their games means cutting out… Uhm, 95% of the publishers out there? Maybe more. I do agree that you always have a choice, but it’s not much of a choice”.

I asked Jinglebell twice for an interview with Crosignani, but he did not reply. Bandai Namco would not comment.

‘If we don’t protect ourselves, no one will’

The video game localisation sector is characterised by very little transparency. It is mainly small agencies that support the recognition of translators. On the other side of the fence, however, not all small independent development studios are aware of the importance of recognising the work of translators and sometimes, even for simple reasons of space in the credits, these are not recognised, effectively limiting the visibility of those people who have worked so that a wider audience could understand the video game.

“There is a share of ignorance on the developer side, which does not realise how crucial localisation is,” said one of the people.

In these cases, it would be up to the agency to insist on or make it clear the importance of recognising people’s work. However, such persuasion is skipped because of a subordination relationship with the client.

It is mainly the big agencies that have the pulse of the sector. “The economic pressure is enough: we are freelancers; all you have to do is stop sending us work,” said one of the people. “You don’t even need to give an explanation. The last thing we want is to displease them. You do the project and wait for the game to come out. And if the developer doesn’t care, you’re not there. And if it’s the agency that didn’t want it, they’re there, and you’re not’.

“So far, I have been happy with Keywords and having so much work, I have not gone looking for other realities,” explained one of the people. “Since I have a lot of regularity, I haven’t even had time to look for other clients. But if I had to go and knock somewhere else, as I couldn’t prove the games I worked on, it would be my word against the company’s.”

One possible solution is to see more and more agencies led by ex-translators, who could, aware of the conditions under which they previously worked, establish a fairer environment and insist that the work be recognised. However, such agencies would still be left out of the larger games, which require a volume of work that is beyond the reach of a small group of people.

“I think another thing working against us – pointed out one of the people – is that I feel like translators are globally people that are shy/don’t want to make a fuss, but if we don’t stand for ourselves, nobody will”.